The following is an article written by David Peterson for Guitar And Bass magazine in Jan/Feb. 2000. Many thanks to David for permission to reproduce the article which can also be seen on the Ampoholics web site.

And many thanks to Paul Goodhand-tait at Ampoholics.org.uk for permission to use the pictures and other content supplied by Ampoholics. Ampoholics is a good source of information and spare parts for various makes of vintage equipment.

THE WEM STORY Part One

For a time during the late 60’s and early 70’s it was unusual to see a live show by a major act or group that didn’t use a WEM P.A.system. Even now, the more powerful systems in present use only differ from Charlie Watkins’ original concept in degree – the basic idea is the same. He can justly claim to be the originator of the modern rock P.A.system, and for most people this would be enough in itself to ensure a place in any music industry Hall of Fame. However this is far from being his only major contribution to it.

Mr. Watkins’ career in the music industry began long before his speaker-towers became a standard part of rock shows and festivals of a decade. In fact he was the first successful British manufacturer of electric guitar equipment, with a virtually uninterrupted line of amps, speakers, combos and accessories that dates from his entry into the market in 1954. With the exception of his big P.A.systems, his products were apt to be overshadowed by other major names of the 60’s like Vox and Marshall. But Charlie Watkins was an innovator, from whose ideas other makers derived their own successful products, and his story will fascinate anyone interested in the origins of the British music equipment industry. He is still very much involved with music, although his commercial activities are not on the same scale as in WEM’s prime time in the 1970’s. He devotes a lot of his time to his accordion playing and associated interests, and in this as well as his business he is ably assisted by June, his wife of 15 years. Charlie and June were kind enough to recently receive Dave Petersen at their home in a pleasant part of South East London, and to provide us with all that we could wish for in recreating the story of Watkins Electric Music.

Charlie would rather be considered an inventor than an engineer, and it’s true that his engineering skill, although deserving of respect in its own right, is most clearly demonstrated in products unique to his own catalogue. But his beginnings in the music industry, such as it was in immediate post-war Britain, were tentative to say the least. Like some other famous figures in the business, they owed much to his experiences during World War 2. “When I was in the Merchant Navy during the war, we were away on some pretty long trips. One of the stewards had an accordion, and he used to sit in the messroom playing it. I thought ‘that’s lovely – I’ll have to get one of them’. So after a bit I got an accordion of my own, and one of my shipmates had a guitar. We had a great time playing together. I used to watch the patterns of his fretboard fingering – that fascinated me. I realised that if you could finger one chord that would give you several others just by moving it up or down the neck. But I could also see how difficult it was to play barre chords. I thought that if you could fit onto a guitar, a bit like a capo, it would make things easier. I even managed to make a couple of rough examples, as best I could with what was available on board, and called it a String Plate. It didn’t turn out to be important in itself, but it’s an example of how my mind was working towards something new, even in those days”.

After the end of the war, Charlie moved back to his native Balham, in S.E London, and put his former pastime to good use. For some months he earned his living as an accordionist, usually teaming up with a guitarist, as in his seafaring days. But he also needed a sideline, and in 1949 began running a record shop in Tooting Market with his brother Reg, who would later play an important part in the story. His knowledge of the live music scene, as well as his own keen interest, also led him into buying and selling musical instruments, mainly accordions and guitars, and the time came when he preferred to hand over the record business to Reg and concentrate on the instruments. To this end he took over premises at 26 Balham High Road. “I carried on selling accordions, as well as records, quite unsuccessfully – I don’t know why, probably because of competition from people like Tom Jennings and Arthur Beller. But I still had this String Plate idea in my mind, and had started making a few, when one of Ben Davis’ (C.E.O. of Selmer ) reps came in one day and showed me one they’d started selling, only better than mine. I only mention it to show that, although the accordion is my favourite, I have always been fascinated by the mechanics of the guitar – how different makers solved the problems of the structure. Gibson, Martin and Macaferri all had different ways of building their guitars, and you could hear the difference.”

“I was also bothered by the fact that whenever I went out and did a gig, you couldn’t hear the guitar properly once there was a bit of an audience. The guitarists tried putting heavier strings on and playing with heavy plectrums to get what they called ‘cut-through’, and this worked for treble, but the sound was very unsatisfactory. Some guitars, such as Gibson, were beginning to appear with pickups fitted, and you could get contact mikes to fit under the strings, but there were no proper amplifiers available – perhaps a few small units for Hawaiian guitars, but nothing good enough to use with normal guitars. Also, guitars weren’t very widely known – people would see one in my shop and ask, how much is that banjo? But I thought it was such a lovely instrument that I wanted to sell them, and find some way of amplifying them. I went to a radio and electronics shop called Premier in Tottenham Court Road, which used to sell amps to use with contact mikes.

Using their unit as a base, I made one that I thought sounded not too bad, an AC/DC unit. I had sold about 20 of them by 1952, when one day I saw a piece in the Daily Mirror about a pop-group guitarist getting killed. Being a fatalist, I thought, its bound to be one of my amps – those AC/DC units were quite dangerous. I sent a telegram to the guy who was making them for me and got him to stop immediately. Somehow I managed to recall all those I had sold and replaced them with safe AC-only units. That has always been my biggest fear – someone getting electrocuted. Amps were used under the worst conditions – dark, pandemonium, wild people bent on having a rave-up! I gave up making amplifiers at that point and just carried on with the records”.

Then in 1955 Skiffle, a hybrid of American folk and country music with a strong helping of rhythm played on makeshift instruments such as washboards and tea-chest basses, mushroomed into a national craze, fuelled by top ten hits from such artists as Lonnie Donegan and Johnny Duncan’s Bluegrass Boys. “I realised that things had changed, and here was a chance to get back into selling guitars. I got on a plane to Germany and went straight to see Hopf, a major distributor of guitars, about the only place you could get a quantity supply from. Anyway, I ordered a hundred folk guitars, more or less his whole stock – he almost fell over! When they arrived at the shop I had trouble string them, there were guitars everywhere, hanging from the ceiling, all up the stairs, you couldn’t move for guitars. But I was just in time – the following week, Ivor Arbiter went over and did the same from another supplier. All the Skiffle players began to come in the shop, among them Joe Brown, and just sit there and play. It was nice music, a bit basic – but now I felt I had to make another amplifier, because the Skiffle guys had the same problem with getting their guitars heard. So I approached Arthur O’Brien at Premier, who had made the power units for my first amps. He was interested in what I was doing, as he played the guitar himself, so I asked him to make what became the first Watkins amp, the Westminster. The first few came out in simple grey-covered cases with sharp corners, like the AC/DC units. One sample I sent out went to Jimmy Reno’s in Manchester. Jimmy called me back, saying he liked the way it sounded, but that the styling looked pre-war (which it did) and he had a few suggestions to make. He told me how I could make the amp more attractive by curving the edges with Bridges hand-router, then using saw-cuts to divide the side panels into contrasting colour areas separated by inlaid gold string. I realised I was talking to a genius – there wasn’t anything like that around at the time. I went out and got the router and made up a few cases to his idea – I did all my own cabinet work in those days. Everyone was knocked out and the amps started to sell a lot faster.”

With this kind of success, Charlie’s ideas began to pay off, and he found himself having to take on permanent staff to keep up with demand. Sid Metherell joined him as works manager and would stay for 30 years, turning his hand to virtually anything that needed doing. Charlie’s brother Reg came in as cabinet-maker. Phil Leigh became the first Watkins sales agent, opening up many new areas. Sadly, Arthur O’Brien, who has been of the greatest value during the development of the first Watkins amps, felt he couldn’t devote the necessary time to Charlie’s flourishing company, and suggested looking for a full-time engineer. The main Charlie found was to have a great effect on the young company’s fortunes.

Bill Purkis, a gifted and experienced electronic and electro-mechanical engineer, joined Watkins Electric Music in 1995. “Bill agreed to join the company on condition that he would get some support for a project of his own, a special record player unit with continuously variable playback speed, designed for the requirements of ballroom dancing. I didn’t mind, in fact I was quite interested, and we actually made about five units. But the contact we had with the people in that business wasn’t a nice experience – they had no time for the technical side of things, and Bill lost heart. From then on he put a lot of effort into supporting my ideas. I’d say he was the most interesting engineer I have ever worked with.” The first item on his job list was to develop a new effect for the line of amps – Tremolo, a recent innovation, the first sound effect ever specifically designed for the electric guitar. Being a feature that tends to be considered “vintage”, it is now a bit neglected. Nonetheless, a good tremolo effect is not straightforward to engineer. A fair example is found in the Vox AC30, which has an excellent effect, but needs three valves to execute it. Bill Purkis designed his circuit around a single ECC83 valve, and it is at least as good – better in some respects.

By 1956, the amplifier range was getting well established, with three models,

Clubman, Westminster, and Dominator, covering the needs of an increasing number of electric guitarists. Charlie’s creative mind was already much in evidence with the novel styling of his amps, the wedge-shaped Dominator being perhaps the finest example.

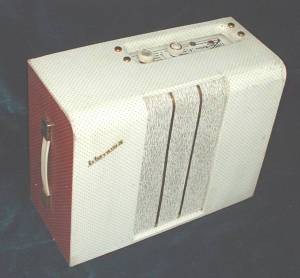

This looks like a Dominator But…. its a Rare 2×10 Westminster which Charlie made for around 6 months or so.

Then came inspiration – he likens it to “a bell that rang in my head”. It was triggered by the account of two customers returning from Italy with a description of the system used on stage by the singer Marino Marini to get the trademark echo effect on his world-wide hit, “Volare”, then high in the charts of most of Europe. It appeared to consist of a pair of Revox tape-recorders, with a long loop of tape running continuously between them. It took a little imagination to realise that one machine was recording the vocal mike onto the loop, the other replaying it a split second later via the P.A.

Charlie went into overdrive, and after discussing with Bill Purkis the various technical possibilities, concluded that a condensed version of the two-machine system, housed in a single casing, would be feasible. The cooking temperature climbed as Bill’s talent for creating compact yet effective electro-mechanical structures condensed the relevant functions of two 15-kilo studio tape machines into a 12” x 8” one-hand portable unit. It got hotter yet when three replay-heads were fitted, using a selector switch to get various combinations. The smoke-alarm went off when a feedback circuit was added, allowing the replay signal to be re-recorded and replayed again, creating a variable echo repeat facility. Charlie knew he had his first real winner. “I had a sample unit shop, to see what the demand might be like, and meanwhile we got busy and built 100 units. I called them Copicats.

Mk1 & Mk2 Dominators, Copycat tapeloop echo…

The day I had planned to put them on sale was a Saturday, and normally there would be a queue up the street waiting for the grocers’ shop on the corner to open – they sold their stuff cheap to clear it before the weekend. I went to open up, and the door burst open with the press of customers – this time the queue was for me! I remember selling the very first one to Johnny Kidd, who wore a patch over one eye. (He made good use of it – Johnny Kidd & The Pirates had a Top Ten single in 1959 with “Shakin’ All Over”, where Mick Green’s guitar has Copicat all over it – ed.) Those first hundred units sold that same day”

“Later, I added some circuitry and made the Mark 2, which was probably the best one ever. I used a Garrard gramophone motor, which cost 12 bob (about 60p, or £6 in today’s money ) and Marriott tape-heads at 7/6d each (40p, or £4 today) – pricey for those days! The mystique of the Copicat really comes from a bit of bad engineering that went into it – I am not going to say what t was. But every firm that has tried to produce their own version would do it faithfully until they came to that art, and couldn’t bring themselves to do it as badly. I am a terrible engineer, and they must all have wondered what I was doing and tried to improve it: but in doing so they lost that special quality”

“The Copicat, Tom Jennings’ AC30, and the Fender Strat were really the three main elements of the 60’s sound. The Meazzi, Binson, and Vox echos that came later were all based on my original idea of a handy portable echo. I sold so many of them that they paid for my first factory in Offley Road, which I bought in 1961. That put an end to all the outwork, and I ended up employing about 40 people there. Also, around this time, my brother Reg, who had been doing the boxes and woodwork for the amps, fancied a go at making guitars. I wanted to be the first maker in this country to have a solid-body guitar, so Reg started making them at a workshop in Chertsey, along with some of the cabinets when it got busy. We didn’t quite make it to having that first solid – Dallas (John Dallas’ company, later Dallas-Arbiter) beat us to it by about a week with their Tuxedo solid, designed by Dick Sadleir, who had written the first tutor I had used to learn the accordion! We ended up making three models, the Rapier 22, 33, and 44, with 2, 3, or 4 pickups. We also had a guitar-organ, which I patented – Vox had a disagreement with Arthur Edwards, who had invented the segmented-fret system they used on theirs, and I got mine patented first. (Vox introduced their guitar-organ in 1965 ). But it was a commercial disaster, none of them really sold – spectacular technically, but after a while the problems began to show.”

“Reg was selling lots of guitars – Bell’s of Surbiton had 10 a month on order, and other dealers were doing much the same. But he wasn’t making much money – he couldn’t even afford to run a car. I said he should make a deluxe version of the Rapier 44, and charge way too much for it – which he did, it was called the Circuit 4, and it outsold the less expensive ones, it was a lovely instrument. He got himself a car, and another factory, but he was so careful and conscientious, and would never charge enough.”

By the close of the 50’s, Watkins Electric Music was a force to be reckoned with in the music industry. It was a one-stop supplier of amps, echo chambers, and guitars, with new lines appearing as fast as Charlie and Bill Purkis could come up with them. Amps such as the HR30 and bigger cabinets like 2 x 12” Starfinder, designed to provide for the bass guitar as well as increased power for 6-string guitars, offered a challenge to the established Selmer company as well as to the comet-like rise of Jennings Musical Industries. In 1961, Charlie Watkins could count his firm among the Big 3 of the U.K. music trade. But there were troubled waters ahead, as powerful forces for change began to make themselves felt both in the music and in the technology used to create it. Al Charlie Watkins’ considerable ability and resources would be needed to survive in them.

End of Part One Editorial copy by David Petersen Jan/Feb 2000

The WEM Story Part 2 – 1961 to 1982

The music business in Britain during the opening two years of the 1960’s could certainly be described as family entertainment. There was a wide variety of music in the charts – styles ranged from commercial folk by The Springfields and The Kingston Trio, the last throes of skiffle from Lonnie Donegan, Elvis Presley-style rock ‘n roll from Cliff Richard and Billy Fury, big-production ballads from Matt Munro and Roy Orbison, country-based pop from The Everly Brothers and Del Shannon, instrumentals by The Shadows, Duane Eddy, and The Tornados, through to revivalist trad jazz from Kenny Ball and Acker Bilk. Helen Shapiro, Petula Clark, Connie Francis and Little Eva represented the girls, in a minority although the opposite was the case in the U.S. , where female artists ruled the charts. Pop music in Britain was the poor relation of show business, controlled by entrepreneurs whose idea of a good time was to have mainly “all-round entertainers” on their books. In this unpromising soil, Watkins Electric Music was somehow able to thrive, as Charlie Watkins’ manufacturing facility was well-suited to the steady demand for his products. The Watkins catalogue by now featured three guitar combo amplifiers, a selection of head/cabinet setups, the Copicat echo unit, and a 30-watt PA system with column speakers, as well as three models of Rapier 6-string guitars, later joined by a bass guitar. “We’d been carrying on with those basic products for three or four years, making a thousand a month of the most successful line, the Copicat, and about the same of the other models combined. Then in 1964 I experienced a sudden drop in sales. I believe this was partly because other makers had started up, but chiefly because the music had changed. The 60’s guitar groups had started getting big, and wanted more powerful amps and American guitars. It all changed from people walking out of my shop with amps and guitars to people walking back in with them. I was wondering what to do – by now I had two factories and they had to be kept busy. I could see the way things were going musically, but there were other problems to deal with”.

One of these problems was that of keeping technical staff on the case. Bill Purkis’ technical flair was offset by a streak of independence that could show itself in unexpected ways. “I had to go away on business for a few days, and when I returned I found production had stopped on one of our remaining good-selling amps. When I asked why, I was told that Bill Purkis wasn’t happy with the aluminium chassis we’d been using and had given orders for no more to be used until stocks arrived of a new steel version, which hadn’t been delivered. Meanwhile there were orders waiting and assembly people doing nothing”. For a time the design work was shared between Purkis and another engineer, Norman Sargent. No-one was surprised when Purkis left in 1963 to set up on his own, leaving Sargent in a difficult situation – further complicated by the latter’s view, increasingly widespread in the music industry, that valve amplifiers would soon be superseded by the new silicon transistor technology. Developments on all sides reflected the efforts of researchers and manufacturers to make use of its promising array of properties, and Sargent was convinced that the future was with solid-state. Charlie, mindful of the success of new 50- and 100-watt valve amplifiers from Vox and Selmer, wanted to introduce a valve amp in this class, but Sargent was so firmly opposed to this that rather than risk losing his only remaining designer of proven ability, Charlie agreed to develop a new range of transistor amplifiers. It should be said that this was well before the advent of heavy rock, and the characteristics that suit valve amplifiers to this style weren’t as important at the time – both Vox and Selmer were actively developing their own transistor ranges. Another powerful attraction was the relative ease of production of amplifiers of comparable output, where a saving of up to 40% in time and cost could be made by using transistors. In 1964 Charlie, now badging his products with a new bright red WEM logo, introduced the Bill Purkis-designed HR30 amplifier, his last valve introduction for years to come, and although production continued of the Westminster and Dominator in re-styled cabinets, these were deemed obsolete, waiting for orders to finally dry up before being struck off the catalogue.

With his company seemingly losing ground, Charlie was looking for fresh business. So when a Los Angeles group called The Byrds, due to tour Britain in the wake of their summer 1965 no.1 hit “Mr Tambourine Man”, contacted him about supplying a PA, he was happy to oblige. Things didn’t go exactly to plan, because The Byrds’ sound, a combination of Beatle-style electric guitars and three-part harmony vocals, asked more of the mike system than the simple arrangement of a couple of 30-watt mixer-amps and two pairs of column speakers could give. “I stood at the back of the hall at one of their shows and realised that the vocals weren’t getting across, and I’ve always felt that if the crowd can’t hear the music properly it’s not worth putting on a show. You could hear their guitars pretty well, as they’d brought their Fender amps over with them, but the mikes weren’t carrying at all. They were intelligent people and after the tour, Jim McGuinn (Byrds’ lead guitar

and vocal – DP) – a nice guy but a straight talker – told me he was happy with the service they’d had but wasn’t willing to endorse my equipment as I’d hoped. I realised then that the music industry was letting down both the groups and the public by failing to provide the means of communication they were all looking for. That tour made an impression on me, and not long afterwards I was in Brussels at a business meeting with my agents in France and Belgium . We were talking about what to do to get some business going, and I mentioned my recent experience with The Byrds’ vocals being drowned by the power of their guitar amps. This was a problem for others in the music business. Attempts were being made to get more powerful PA, usually by using big valve amps, but it was obvious to me that these were much better for guitars than for mikes. Both my dealers – Alain Le Meur, the French agent, and Albert Verriest, the Belgian – were quite technical, and we talked about making a system from about a dozen high-powered hi-fi amps driven by a common mixer. That bell went off in my head again! When I got back to England I got Norman Sargent in and described the idea to him, based on using the RCA power stage we’d been looking at to make a 70-watt guitar amp. He said it would be possible to couple up four or five – ‘slaving’ was the word he used for the first time I’d heard – and I said I was thinking of more like twenty. When he’d recovered a bit, he said he didn’t really see why not. I said ‘you’ve got a week’ – and he did it!”

This phase of the story is best suited to show how Charlie Watkins’ commercial brilliance feeds from his feeling for music. His early musical experiences had left him with a strong interest in the problems of getting a performance across to an audience, and this led him to manufacture amplifiers. Amplified instruments now seemed to be biting the hand that fed them, and Charlie was looking for a way to correct the balance and give singers, fighting for position with the arrival of the electric guitar, something to fight back with. This became possible only by the use of transistors on a new scale – Sargent’s enthusiasm for solid-state provided the building-block that Charlie would use to support WEM’s recovery from the lean times and a climb back to music industry supremacy. It’s unlikely that his idea would have been practical without the economic but reliable SL100 slave amplifier that gave enough flat-response, low distortion audio output for it to work. The properties that suit valve amplifiers to guitars, particularly their habit of interacting with the speaker in a random way, become a nuisance when used in mike systems. Here, a tightly-controlled amplifier/speaker relationship and a relative freedom from peaks in the system get the best results – hence the hi-fi amp concept of Le Meur and Verriest. The SL100 was simply an affordable means of providing these qualities – meanwhile all that remained to be done was to check the idea in practice by testing an actual system. “We put together a system at Offley Road with one of my Audiomaster mixers that everyone in the industry had been laughing at, and some SL100’s driving two 4 x 12” columns each, then ran a test. I brought up the power gradually, and things were running nicely up to 300 watts. When I switched in 400, some of the girls from the top floor came down crying, and Gordon Shepherd the works manager had a speaker fall off its shelf and hit him on the head. Next thing, the police were at the door with a complaint from the locals, so I had to switch off. I was fortunate to have someone working for me at the time who could see the value of it – John Thompson, he’s well-known in the business now. He said ‘you’ve got something there Guv, all it needs is somewhere to show what it can do’. He was working part-time at the Marquee as a bouncer or something like that, and he said he’d mention it to the owner, Harold Pendleton. This man also happened to be the organiser of the Windsor Jazz Festival, and I asked if we could run my system there. He agreed, because the audience wanted more rock groups, and all they’d had for PA the year before was a couple of 100 watt stacks which had been a disaster. But he also made me guarantee it would all work on the day. That was very much an instance of being in the right place at the right time. All these new groups – Ten Years After, The Who, Fleetwood Mac, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin – were queuing up waiting for a chance to play. We set up two mixers, which gave us ten channels, with ten slaves and twenty speaker cabs. The top act at that year’s festival was Arthur Brown (no.1 in the chart in August 1967 with “Fire” – DP), but the first act to go on was Donovan. That gave us a chance to get going gradually – lucky, as we found out early that we needed an input pad on the mixers, which hadn’t been fitted. Everything was distorting, and it could have been disastrous. Fortunately Norman Sargent was there, so he and Mick, the Marquee technician, rushed off to Curly Hunt’s music shop in Windsor, got some pots and a bit of plywood, and made up a pad for each channel. It saved the day – all mixers have them now. Night-time came, and we’d started gently with 200 watts, but now Harold Pendleton came over and asked for some more level. I switched in 400 watts, then he seemed concerned that this might be overdoing it, and I told him that wasn’t even half of what it could do. Next thing I knew, the Mayor of Windsor, The Chief of Police, the Noise Abatement Society – anyone anti-noise, they were all there. Then on came Arthur Brown – I was putting out 600 watts by now, more to see what the system could do than anything else. There’s a point in his big hit “Fire” where he screams at the top of his voice, and I told John Thompson , when that scream comes, throw it all in with full reverb. The best sound I ever heard in all the years I did PA was when that happened – I thought, this is how it should be! The crowd went mad – but then the constabulary showed up. ‘Are you responsible for this equipment, Mr. Watkins?’ ‘Yes, sir’ ‘Well I shall have to ask you accompany me to the police station to

discuss this matter’. I thought, Christ, he’s arresting me. With all those other officials on his back I suppose he had to arrest somebody, so I said, ‘All right, I’ll come along, but before I do, I’ll tell my people to shut down the system” The prat of a man said, ‘That’s exactly what we want’, and I said ‘It might be what you want, but there’ll be 40,000 angry people out there rampaging through Windsor – what will you do about them?’ That policeman didn’t get his job by being a complete idiot – he knew that with the mood of the time, Flower Power, a lot of anti-police feeling with the drugs thing, it would only need something like that to give him a big problem, so he said ‘Perhaps we should discuss this at some more convenient time’, or words to that effect. So the show went on. But they did take me to court afterwards”

“When I heard I was to be prosecuted, Harold Pendleton told me he’d look after me, and he was as good as his word. I was up before Reading Crown Court, and they were trying to get an order to restrain me or anyone else from using that system again. He got Quintin Hogg QC, who became Lord Hailsham, to defend me and he was brilliant – he could get to the real business of something as technical as mine and make his legal point with it. You might think this was a lot of fuss about 1000 watts – they use as much as that for foldback nowadays. But you’ve got to remember that nothing like that had been used since Nuremberg .” (1936 Nazi Party rally with a crowd of over 100,000 – DP).

Charlie had a narrow escape from his brush with the authorities, which could have put him out of business, and this was the last time his system was used in a populated area – from now on, open-air festivals were held at a distance from towns of any size. But the pattern was set, and WEM systems varying in power from 1500 to 2500 watts provided the sound for all the major festivals of the new decade, most famously at the Isle of Wight Festival and the Stones concert in Hyde Park in 1969, which Charlie rates his best achievement in sound quality. Others include Bath in 1970, Lincoln in 1971, and lastly at Grangemouth in 1974 where 4500 watts were used. For five years WEM PA’s dominated stages everywhere, but it wasn’t all easy going. Big crowds can cause big problems and towards the end of the festival era of the 1970’s ugly confrontations between heavy-handed security staff and excitable festivalgoers became more common. More than once Charlie’s crew were caught in beer-bottle bombardments and he was badly concussed at one such incident at the Bath festival. The added uncertainties of wind and weather, sometimes causing the sound to fade if the wind shifted direction, and the increasing demands made on the system itself made it a relief for him when the fashion for rock festivals died as quickly as it had arisen. They’ve become popular again in the last few years, but technology and facilities are in a different category to the 1970’s.

By 1975 Charlie was beginning to feel he had made his point. With twenty years of success in the music industry to look back on and all his major goals achieved he began to downsize his business enterprises. His health had begun to suffer, as had his domestic life. Worse than this, he felt isolated in his position at the head of his company, with few he could call on for executive support. He’d employed good managers from time to time, but those he would have liked to advance in the company seemed to get more tempting offers. Without this essential link he had less personal contact with his workers than he would have liked. “I remember one particular year at Offley Road when we shut down as usual while everyone went on holiday. I chose that date to go into hospital with a bad thyroid problem I’d been having. I got out the day before they all came back, so I was at my desk as usual. When they came in, all brown and cheerful, no one asked me how I was! I thought then, this isn’t what I want. It’s all right while you can stay on top of things, but when you’re not really up to it it’s not so funny”. Business was healthy, with small and medium PA rigs selling well and the Copicat in its updated transistorised form still a firm favourite. There was also a more potent 50-watt Dominator with reverb, still considered one of the best sounding WEM models. But Charlie’s heart was no longer in the business – he began to spend more time in the development shop, leaving things to run any way they would on the production. The guitar business changed names and proprietorship, initially to “ Wilson ” and then to “Sid Watkins”, reflecting brother Reg’s departure from the business. The Offley Road factory, and WEM as the industry and the public had known it, closed its doors in 1982. Charlie took some much-needed time out of the business, rediscovered his early love of the accordion, and remarried in 1985. “When you’ve got a lot of people around, you can forget your own life. I decided to live my own life at last. I still make my Copicat, and some accordion equipment, but with a minimum of help, and I’m happier like that – never been happier than I am now!”.

Charlie Watkins still loves the music business, and with his active mind and the phone ringing constantly, don’t be surprised if you see WEM in your music shop again one day. It would be a welcome return.

© David Petersen March 2000